Firefox • Chrome • Safari • Opera • Explorer

It's almost like the old days. As the Web was being developed, many browsers were available. Then the choices dwindled essentially to Explorer and Netscape. Opera was there, but with only a tiny market share. Firefox (and other browsers based on the Mozilla engine) came along. Then Chrome and Safari. For some of us, the best answer to "Which browser should I use?" is "All of the above."

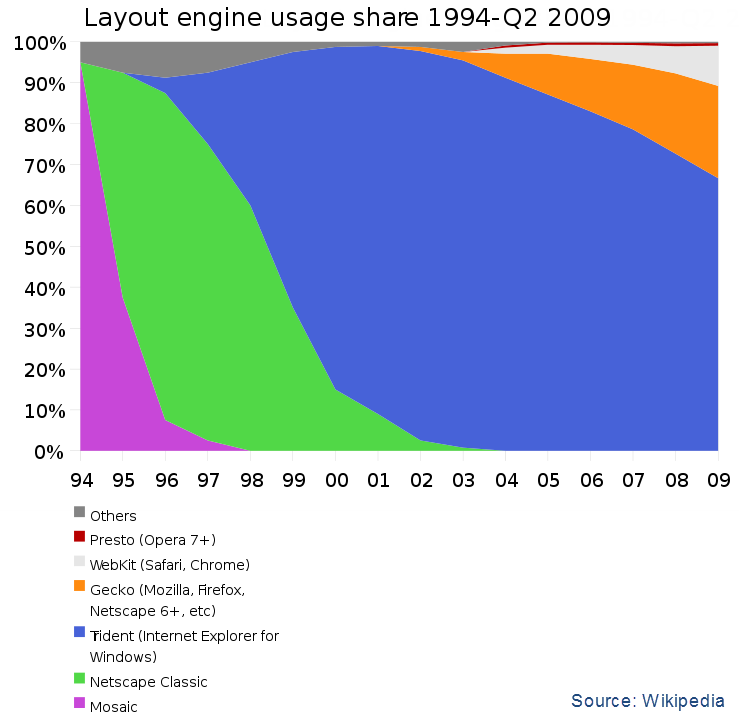

Really. Wikipedia has a useful graphical time line of browser development.

Most of the early browsers are forgotten. They had names like ViolaWWW, Erwise, MidasWWW, MacWWW. Clever names, those. Then Mosaic, Cello, Lynx (a character-based Web browser), and Arena. Netscape Navigator was followed by a totally useless Internet Explorer. Explorer was slightly improved by version 2, but it wasn't until version 3 that Microsoft had a more or less usable browser. That was in 1996. At that time, about 36 million people were using the Web. Today it's more like 2 billion.

Initially, Mosaic had virtually all of the market, but Netscape arrived and took over. When Microsoft bundled its browser with Windows, IE became the leader. Since about 2007, Mozilla-based browsers, Safari, and even little Opera have been chipping away at Microsoft's dominance. (See chart below.)

Which is Right for You?

Possibly a combination is best.

For example, my preferred browser is Firefox because thousands of add-ons are available and these allow me to configure a browser that does exactly what I want it to do. Firefox can also check for updates (its own and updates for the add-ons) when it starts. This is good because it keeps all components up to date, but it also can make the start-up process slow.

For that reason, although Firefox is my favorite browser and the one I use most often, it's not my default browser. That's Chrome. If I click a link in an e-mail, I want the browser to open quickly and Chrome is the speed champion. Chrome also has some other advantages by creating a new instance for every website. If one site causes a browser crash, only the single instance crashes. Most of the time.

As with most things from Google, Chrome is essentially beta software and features arrive and depart with little warning. But Chrome is collecting a following of developers who create add-ons. Nearly every add-on that I use with Firefox is available or has an analogous add-on or the feature is already built in to Chrome.

Microsoft will soon release version 9 of its browser. Honestly, I have to admit that version 8 has some good features, but IE is probably still the most security-challenged browser. I haven't yet looked at the IE9 beta but will undoubtedly install it when it's released. You need IE even if you use it only rarely: IE has a direct link to Windows Update and it's also the only browser that works for certain websites that have been created by non-thinking designers.

As much as I admire Opera's objectives, I haven't been able to use the browser on a long-term basis. There are simply too few customizations and the rendering engine seems to have too many quirks.

That leaves Safari and my previous opinion of the Apple browser that's based on the WebKit Open Source Browser Project had been that it's an OK browser for Apple computers but should be avoided by Windows users. Since the release of Safari version 5, my opinion has changed. Safari has taken the place of Opera as my number 3 browser.

At the office, I typically have 2 browsers open, one on each screen. At home, I open Firefox as soon as I start the computer, but Chrome is almost always open because I've followed a link from somewhere. In cases where I need a third browser. I'll reach for Safari. And on rare occasions (when I must use Internet Explorer) you might find me with 4 active browsers.

So you don't have to pick just one.

Firefox #1

Firefox #1

Without question, Firefox is the versatility champion because of the huge number of add-ons that are available. The add-ons can improve security, modify the browser's look and feel, add blogging and commenting abilities, assist website developers with code testing tools, help with shopping, streamline downloads, and more.

Chrome #2

Chrome #2

A close second in terms of add-ons Google's Chrome browser is probably the fastest-loading browser available. If you routinely need to have a second browser open and you don't want a second instance of Firefox, this is a good choice. And Chrome, of course, integrates well with Google's other offerings.

Safari #3

Safari #3

I'm more than a little surprised to find myself writing anything complementary about Apple's Safari because it tends to be an also-ran even among die-hard Apple fans. The current version is far more capable than previous versions and its speed rivals that of Chrome. This wouldn't be my choice as the default browser, but it's now pleasantly surprising instead of scary.

Opera #4

Opera #4

Opera has never really caught on anywhere and in the US, it's almost unheard of. The browser has add-ons, but not a lot of them. What's available is often not very useful and many add-ons perform the same tasks. At 10MB, Opera is still the smallest browser to download. Opera might be a good first choice for those with slow connections because a "turbo" setting can boost download speed by compressing data and image traffic on Opera's proxy servers and then delivering compressed files to your browser.

Internet Explorer #5

Internet Explorer #5

The number one browser is Internet Explorer, apparently because it comes with Windows. It's not the best. It's not the fastest. It doesn't have the largest number of add-ons. It's not the most secure. So why (I keep asking myself) is it still the number one browser?

If it Happens, They Won't Call it MicroDobe

Is Microsoft thinking about acquiring Adobe? The irony would be rich because a significant part of Adobe's growth has come from carefully considered acquisitions. The New York Times says Microsoft's CEO Steve Ballmer has meet with Adobe's CEO to discuss competition with Apple. Rumors sent Adobe's stock up, then down. My first thought was that this would be a very bad match. On second thought, I'm not so sure.

There were rumors, several years ago, that Microsoft was thinking about acquiring Adobe, but it never went past the talking stage. With Apple trying to lock Flash out of its mobile applications and Google trying to replace Microsoft Office, both companies could benefit from the combination.

But what about users?

Microsoft is unjustly criticized for being a copy-cat. The company has come up with a number of innovations over the years. And although Microsoft often doesn't get things right the first time around, what software developer does? After 10 years of OS-X, Apple has an excellent operating system; but Apple started with a fully-functional version of Unix as the operating system's back end and added the graphical front end. Even so, OS-X 10.0 was useless.

Users might fare reasonably well if the companies merge. For Adobe to have better access to the operating system's internals would be a plus to Adobe. For Microsoft to have access to Adobe's graphics engine and typesetting prowess would be a plus to Microsoft.

The threat to Adobe comes from Apple's photo editing application (Aperture) and the video editor (Final Cut). These applications aren't available on Windows PCs and most graphic designers use Macs, so the threat is real even though many graphics professionals consider Apple's programs to be substandard now. Adobe's applications are available for both PCs and Macs and that alone is enough to keep Microsoft in designers' minds.

A merger would allow Microsoft to dump its Flash competitor, Silverlight, and the combined companies could concentrate on competing with HTML5, which could threaten both Flash and Silverlight.

Some technologies would win and others would lose, but Adobe is good at playing this game. Following the merger with Macromedia, some Adobe products survived and some Macromedia products survived. Adobe Illustrator instead of Macromedia FreeHand and Macromedia Dreamweaver instead of Adobe GoLive. Similar decisions would be needed if Adobe and Microsoft become one: Silverlight or Flash? ASP Net or ColdFusion? Adobe PDF or Microsoft XPS?

Adobe is a big company and the acquisition would be expensive. The number $15 billion has been mentioned. If Adobe is big, Microsoft is huge. $15 billion isn't a huge amount of cash to a company that makes more profit every year than many nations' gross domestic product. Microsoft could acquire Adobe in a friendly or hostile takeover.

I have met product managers from both companies and there are similarities: They are fiercely loyal to their applications but they are willing to listen to suggestions. But below the surface, differences are inevitable. Developing graphics, publishing, and video applications differs considerably from developing operating systems and office applications. When Adobe acquired Macromedia, Macromedia disappeared because both companies had a lot in common. If Microsoft acquires Adobe, I would hope that Adobe remains as a more or less free-standing operation.

So although my first thought was "OH NO!" when I heard that there was once again discussion of an Adobe acquisition by Microsoft, it now seems that there might be some promise in a small house of mud.

Short Circuits

AOL to Buy Yahoo?

Yahoo's stock price jumped more than 15% on Thursday when reports began circulating to suggest that AOL (or maybe News Corporation) would buy Yahoo. That's now being characterized as nothing more than a trial balloon. Even Yahoo claimed to have heard about the plan only from reporters.

AOL has a history of buying high and selling low. And AOL is now worth about 1/10th of what Yahoo is worth. AOL is valued at $2 billion while Yahoo's value is pegged at $20 billion.

Some of that worth comes from its 39% ownership of Alibaba, the largest Internet service provider in China -- about $12 billion of Yahoo's worth, in fact, is tied to Alibaba and the company is reported to have little interest in selling now.

Still, the story sold some newspapers on Thursday.

BG, Phone Home

Steve Ballmer held one up, but you can't buy it yet. The Windows Phone 7 mobile operating system was the subject of Ballmer's presentation this week. You can buy a Windows Phone from AT&T starting in early November, from T-Mobile before the end of the year, and sometime next year from Verizon and Sprint. To start, 3 phones will be available, each a $200 device. By sometime in 2011, that number will increase to 9.

Dell, HTC, LG, and Samsung will make Windows Phones. Ballmer says some will have keyboards and some won't. Microsoft has had the phone in development for 2 years and really wants to get into the smartphone market.

Above: Ballmer flogs the phones.

At right: A Windows Phone 7 with e-mail

Microsoft's first-generation phones had begun to catch on when Apple released the Iphone. Sales tanked. Earlier this year, Microsoft released the Kin, a poorly-named phone aimed at younger users. (What teen would buy a phone called the "Kin"?) At it turned out, teens didn't buy the phone. Nor did anyone else. And after less than 2 months, Microsoft cancelled the product.

Conventional wisdom (or maybe urban legend) says that Microsoft has to try something 3 times to get it right. The new phone would be the third try and Ballmer highlighted features that he said company designers developed based on research into how people use phones when they're mobile.

The new phones will play well with Zune (for music and video), Bing (for search), OneNote (if they get this right, I might be in the market for a phone), and even the Xbox 360.

Speaking of Phones: The Industry Doesn't Want This

The FCC says it would like consumers to be notified when they're about to use their cell phones in a way that will cost them a lot of money. The cell phone industry, which is always entirely up-front and honest with consumers about billing, usage, and long-term contracts says the industry is doing just fine by self-regulating and the government should stay away.

By "just fine" apparently they mean that they think it's OK to allow someone who has a $40 per month plan to unknowingly rack up a $1000 monthly bill by failing to notice a microscopic "roaming" icon on the screen. Or to place keys in such a way that it's easy to fire up the Web browser accidentally (at $2 per incident). If you have a cell phone, you've probably encountered "bill shock" at least once.

The FCC says that the industry should warn people when they're about to use the last of their monthly plan's minutes or messages or that it might be reasonable for cell phones to be a bit more clear about when the user is in a "roaming" area that's subject to high fees.

An example from the FCC files: A retired 66-year-old marketing executive from Massachusetts was billed $18,000 after his mobile service's free data downloads expired. The user had received no warning but, once The Boston Globe wrote about the incident, the cell phone company agreed to cancel the bill.

Yeah, that "self-regulation" thing sure was working out well for that user.

Cell phone companies have an interesting definition of "unlimited", too, because virtually all "unlimited" data plans come with limits. If the plan has limits, a reasonable person might expect that it wouldn't be called "unlimited". The FCC seems to think that would be a good idea, too.

Cell phone companies have hardware and software that can track cell phone usage by the second, by the data byte transferred, by location used. Surely that technology could be set up to notify consumers when they're approaching a limit.

Of course government is bad and self-regulating private enterprise would never let anything bad happen to consumers, so this power grab by the FCC should be resisted.

Shouldn't it?

The author's image: It's that photo over at the right. This explains why TechByter Worldwide was never on television, doesn't it?

The author's image: It's that photo over at the right. This explains why TechByter Worldwide was never on television, doesn't it?